Mount Kilimanjaro

Getting to the mountain, though, proved to be a difficult task in itself. As would become a theme during our time in Africa, the poor infrastructure delayed our traveling. We landed in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania's biggest city, and took a bus to Moshi, a moderately sized town sitting in the shadow of the mountain. On the main (and perhaps only) "highway" from Dar Es Salaam to Moshi, a mere two lane road, a truck jackknifed and backed up traffic for miles. After some time had passed we decided to walk on ahead to the accident and see what was going on. There we saw hundreds upon hundreds of people standing around, clueless about what to do. Even the military, armed with tow trucks and cables, seemed unable to offer any relief. This type of scenario, we were told, was not uncommon.

|

|

|

|

Determined to make the most of our delay, I walked to a nearby village to talk with some of the children, pictured here in the third image above. One boy had made a bicycle out of wood, and in the background you can see their mud and thatch housing. The fortunate ones had tin roofs. Eventually the truck was moved and we made our way across the beautiful African landscape, arriving in Moshi after sundown and over eight hours after setting out.

The next morning we set out in a packed car to the base of the mountain. Along the way we passed several villages made of timber huts (pictured left) around the mountain. In spite of the rigors of being a porter or guide, it is one of the best paying jobs in the area and people would clamor for the opportunity to be hired. On the right is our full troupe, with chief guide "PrayGod" sporting the green and blue hat. For the two of us trekking "clients" we had a total of 8 support people, including the two guides, a head cook, a "waiter" for our meals, and porters. The trek would have been impossible without them.

The next morning we set out in a packed car to the base of the mountain. Along the way we passed several villages made of timber huts (pictured left) around the mountain. In spite of the rigors of being a porter or guide, it is one of the best paying jobs in the area and people would clamor for the opportunity to be hired. On the right is our full troupe, with chief guide "PrayGod" sporting the green and blue hat. For the two of us trekking "clients" we had a total of 8 support people, including the two guides, a head cook, a "waiter" for our meals, and porters. The trek would have been impossible without them.

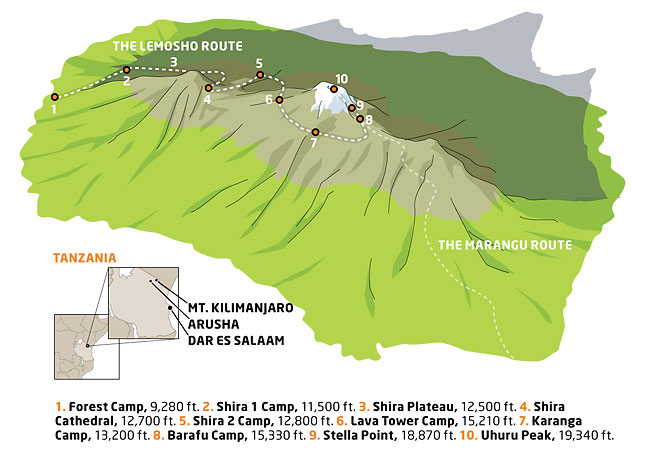

We set out to scale the mountain on the Lemosho Glades route, one of the toughest and least used routes on Kilimanjaro. We selected this route because it's relatively unspoilt, and also because the descent is a different path than the climb. Lemosho is generally more difficult than other routes, and it often takes more time. It isn't uncommon for trekkers to allot 7 to 11 days, yet we (perhaps foolishly) decided to do it in six. Very few others choose to do it so quickly.

We set out to scale the mountain on the Lemosho Glades route, one of the toughest and least used routes on Kilimanjaro. We selected this route because it's relatively unspoilt, and also because the descent is a different path than the climb. Lemosho is generally more difficult than other routes, and it often takes more time. It isn't uncommon for trekkers to allot 7 to 11 days, yet we (perhaps foolishly) decided to do it in six. Very few others choose to do it so quickly.

We arrived at the Londorossi Gate around noon. At the gate a park ranger weighed all of the porter loads to ensure that no porter carried more than 20 kilograms, but even this is quite a load to take up. The rule helps prevent abuse of the porters by companies trying to get by as cheaply as possible. Of course, we wouldn't lump gatwick hotels and their porters with twenty kilos of luggage, but you would be surprised at what some companies offer for minimal prices, and it's reassuring to know the porters here are being kept from dangerously over-exerting themselves. The first day was only a 2 hour hike. It took us through a beautiful rainforest where we saw some Colobus monkeys in the trees above. We were also able to bond with our guides PrayGod and Honest. We loved teaching each other songs from our native lands, although we all knew Kumbaya. They also began teaching us Swahili, which would turn out to be invaluable during the rest of the trip. Finally we reached Mti Mkubwa (Big Tree) campsite at 9022 feet (2750 meters).

|

|

|

|

After a hardy breakfast prepared by chief cook Pasat (a Swahili nickname given for his speed up the mountain), we set out on the second day. Slowly the trees began to change and then, quite quickly, the "Rain Forrest Zone" changed to a "Moorland zone" consisting of mainly smaller shrubs and bushes. This gave us the first opportunity to begin to take in the mountain's size and scope (see third picture below). By lunch time we had climbed over 2,000 feet and arrived at Shira 1 camp, sitting at 11,483 above see level. In the fourth picture below you can see Carson sitting at this camp with the mountain rising into the clouds behind. Our guides told us that in the 1980s one could usually find snow throughout this camp, but now it never reaches that far.

|

|

|

|

But after just four hours of hiking we were still only halfway into the second day. The final portion proved to be long and tiring. Uphill portions were very steep, the air continued to thin, and the temperature kept getting colder. Thankfully it didn't rain, but the sweat and dirt served to make conditions a bit uncomfortable. After what seemed like an eternity, we arrived at Shira Hut that evening, 12,598 feet high. Although there had been some signs of altitude before, we really began to feel the effects here. Both of us had headaches and Carson began to run a fever. Shira Hut, featured in the three pictures below, sat on a high ridge with little vegatation around it. It's one of the highest plateaus on earth and offered a clear view of the mountain and the challenges ahead.

|

|

|

The night of the second day we considered adding an extra day to the climb to help us adjust, but after sleeping we were rejuvinated enough to soldier on. In spite of our altitude we were still able to see plenty of interesting vegetation. In the second picture below Carson stands under a giant "Senecio", which were quite numerous at parts. In terms of health I took plenty of vitamins and we always kept drinking water. Dehydration is generally considered the number one reason people fail to make it to the top, so most recommend drinking 4 liters a day. With a camel pack that's easy to do, but it has the unfortunate consequence of making you get up several times each night (in the cold) to pee. The fourth picture belows shows PrayGod and Pasat. Pasat's method of carrying food/gear on his head was relatively commonplace. He was lucky enough to have a radio as well.

|

|

|

|

At about halfway through the third day we arrived at Lava Tower, pictured first in the set below. This was roughly the same part that trekkers coming up from the Machame Route joined us, and the from here on out we began to see more climbers. Climbing Lava Tower isn't a necessity; trekkers have the option of simply walking around it. But climbing to the top is a good challenge and it has the added benefit of helping you acclimatize better. So the two of us, along with PrayGod and assistant guide Honest, forced our way up. The second picture below shows me in one of several precarious situations trying to manuver my way around. But we did make it to the top (picture three below) which reaches 15,092 feet, and then began the slow descent down to Barranco Hut. The belief is that sleeping at lower altitudes than you reach helps your body adjust and create red blood cells.

|

|

|

|

That evening we were happy to reach Barranco Hut, which at 12,959 feet is over 2,000 feet lower than Lava Tower. But the relief was tempered by the view of what awaited us the next morning. Like an imposing fortress, a massive volcanic rock wall - called "the Great Barranco" - was right in our way. And we were to go right up it (pictured 1st and 2nd below). Most sections turned out to be a straightforward mountain trail, other parts were more difficult, but all of it was taxing on my muscles and lungs.

|

|

|

|

By the time I reached the top of the wall I wanted to vommit. I tried unsuccessfully several times. PrayGod told us that throwing up makes you strong, but my stomach seemed to disagree. Worse, after overcoming the wall, we still had hours of hiking ahead of us. I was exhausted and part of me began to wonder whether I would make it. But the rest of the day took us through the relatively flatter Karanga valley and we knew the end was near. Karanga Valley (fourth photo above) is the last place on the route where water can be found so the porters had to carry water to the next campsite, Barafu.

At lunch on the 4th day we were cold and exhausted. The food prepared by Pasat was always superb given the circumstances, but the altitude caused us to lose much of our appetite. Worse, Carson is allergic to avacado and inadvertantly ate soup with it in it. Vommitting came to the rescue and helped him fight through it. By the time we reached Barafu camp (15090 feet) I was in a daze and felt like I was on another planet. There was little oxygen in the thin air for my brain and muscles and the sheer exertion from the hiking had drained me of energy. It was very cold and very rocky.

We got to sleep at 8pm that night, but it was more of a nap than any type of meaningful rest because the final ascent began in just 4 hours at midnight. And as always, our rest was interrupted by countless pee breaks. As we set out in the dark at midnight with our headlamps, doubt kept creeping in. Would I make it? What would people think if I turned back now? The route kept zigzagging and after an hour or so got increasingly sandy. It seemed as though for each step I took I'd slide back half of the way. My breathes were labored and I was stopping for short breaks every 5 minutes, if not more. Unfortunately this caused Carson to have to stop as well, and once you stop moving the cold bites even harder.

In some ways I was in a trance, but I could still sense the eery feeling that I was going to blackout at any moment. I told myself that if I passed out I'd turn back, but that moment never came. We'd later learn that on the very day we were ascending the summit a 23 year old French girl died at Barafu camp, and another person had died the day before that. I'm sure that had we known that before our ascent, my resolve would have been weakened. There were undoubtedly moments when I felt like death was a real possibility for me as well, and knowing it'd happened to others would've highlighted the fear.

This last day or so was also quite spiritual for both Carson and I. We came to understand the strong Christian faith of our guide PrayGod, and through all of the challenges it really struck home that I did not do this alone. Only through God's will, and help from the guides and Carson was I trully able to reach the summit. But reach it we did and it was one of the most tremendous feelings of satisfaction I've ever felt. Below are four pictures from the top of the crater, with the second one being at Uhuru Peak, 19,340 feet above sea level.

|

|

|

|

We were cold and exhausted, but the thrill of reaching the top had given us a momentary boost of energy. It was a good thing, too, because after 3 or 4 hours of hiking back to Barafu camp, we got only 1 hour of rest before hiking another 6 hours downhill to Mweka Hut. In the course of one day we descended nearly 9,000 feet and our joints could feel the pain. Below in pictures one and two are images of our tent that night. Even though we'd become pros at sleeping in it under all conditions, our clothes and bodies had become unbearably filthy.

|

|

|

|

On the last and final day on the mountain each step seemed to bring just more mud. The third picture of above shows the long muddy stairway that was what constituted most of the descent. Our feet and knees were taking a beating as well. The last picture above shows children from a nearby village walking up as we approached Mweka Gate. Some children have wisened up to the tourists' desire to photograph natives, so they purposefully cover their face unless they're paid money. Here the girl on the far right can be seen doing that.

At Mweka gate we were given certificates and then gave tips to all those who helped us. Leaving the mountain was bittersweet. It seemed as though every fiber of my being had been tested and pushed to limits I never even knew existed, so getting back to a hotel for a real shower and bed was going to feel like paradise. But I also knew that I was leaving an amazing place that had given me experiences most people get only in dreams.

Just a few days later while we were on safari we learned that the owner of our guide company had committed suicide by jumping from the top of a building. Fortunately our amazing guide PrayGod rebounded and now has his own company called Peaks & Plains, and I would encourage anyone considering a Kilimanjaro climb to contact him. We encountered a number of guides during our climb, but I never met one better than PrayGod. To email Praygod Munguatosha just click here. For more questions for us click here to contact us. Mt. Kilimanjaro is an amazing place and with the right preparation and mindset you too can experience its magic.